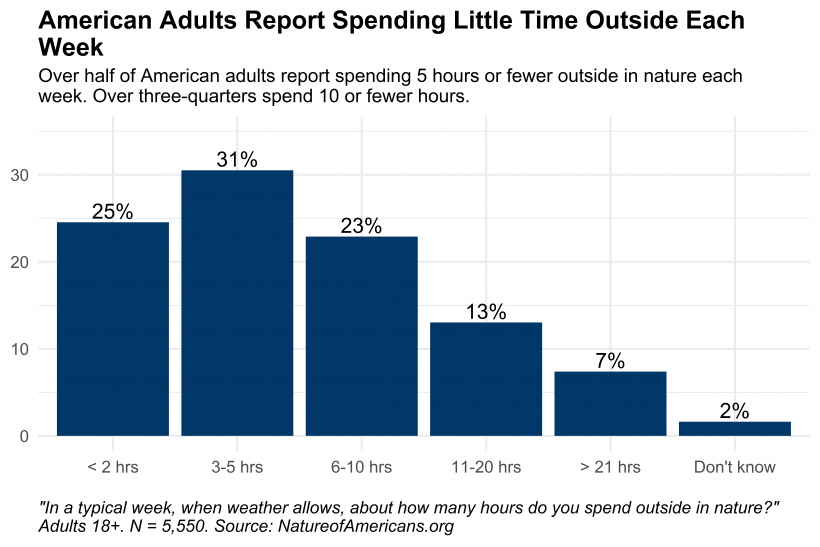

We all know the numbers, yet we live like we don’t. Technology connects us to headlines, to feeds, to outrage. But it does not guarantee that we feel the ground beneath our feet. More than half of American adults report spending five hours or less in nature each week. Parents of 8–12-year-olds report that their children spend far more hours with TVs and computers than playing outside.

That matters because this disconnect has an emotional cost. Climate worry is not abstract anymore. Large surveys of young people show widespread climate anxiety, with many saying the worry affects daily life. The Lancet survey of 10,000 people aged 16–25 across ten countries makes that plain. Research by psychologists, including Susan Clayton, ties climate change to real mental-health harms: stress, depression, trauma. The Lancet

I started a small field project in Kotte because statistics are one thing, and standing on the floating deck looking at the reeds is another. Beddagana Wetland Park sits inside Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte. It is listed at roughly 18 hectares and is a real urban refuge.

It holds a high number of resident and migratory birds (roughly 80 species reported by local wetland initiatives), about four to five dozen butterflies, and evidence of cryptic mammals like the fishing cat. The site also performs practical jobs: flood buffering, water filtration, and local cooling. But it is fragile. Dumping, construction, invasive plants, and fragmented oversight keep the wetlands under pressure.

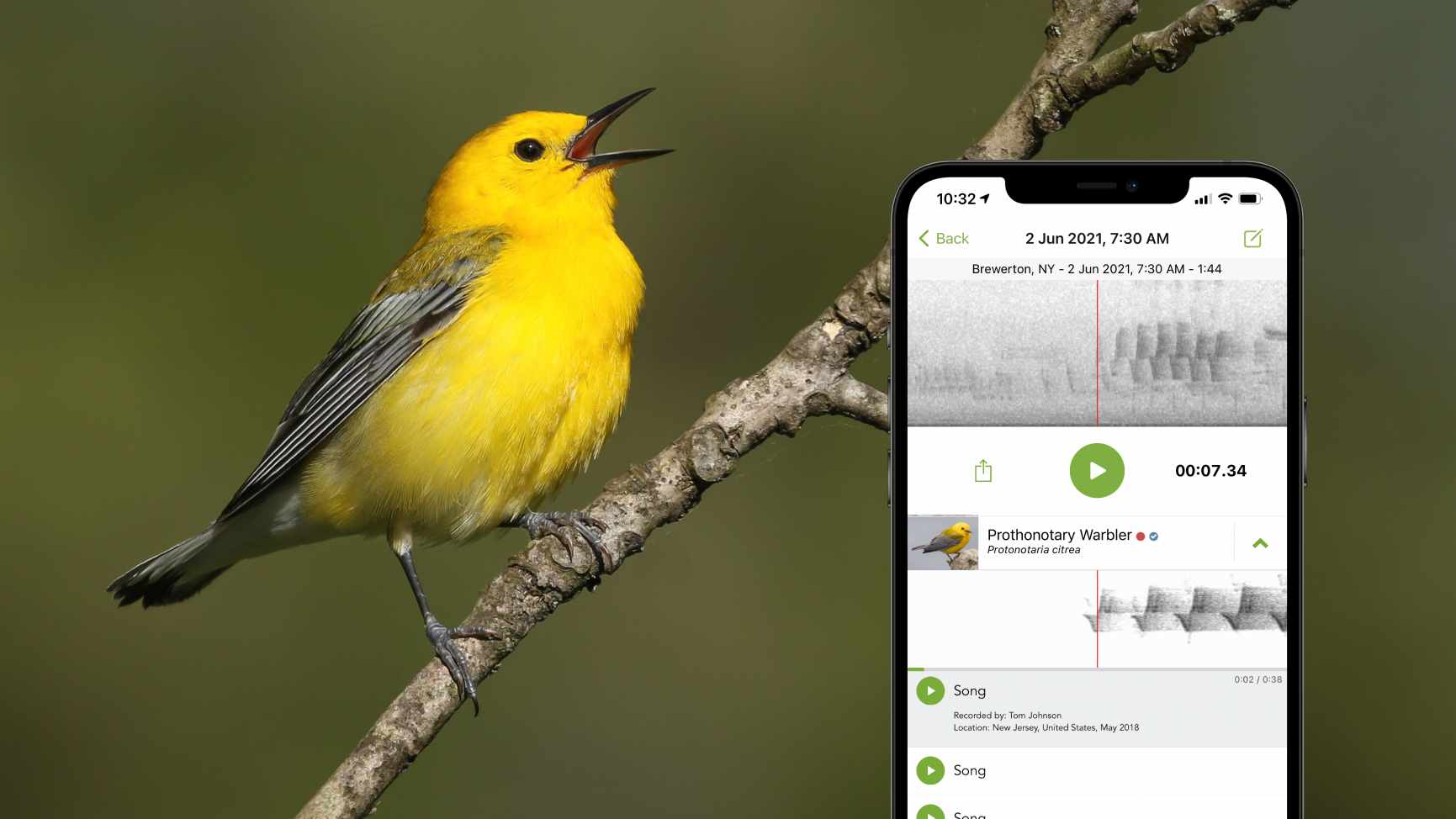

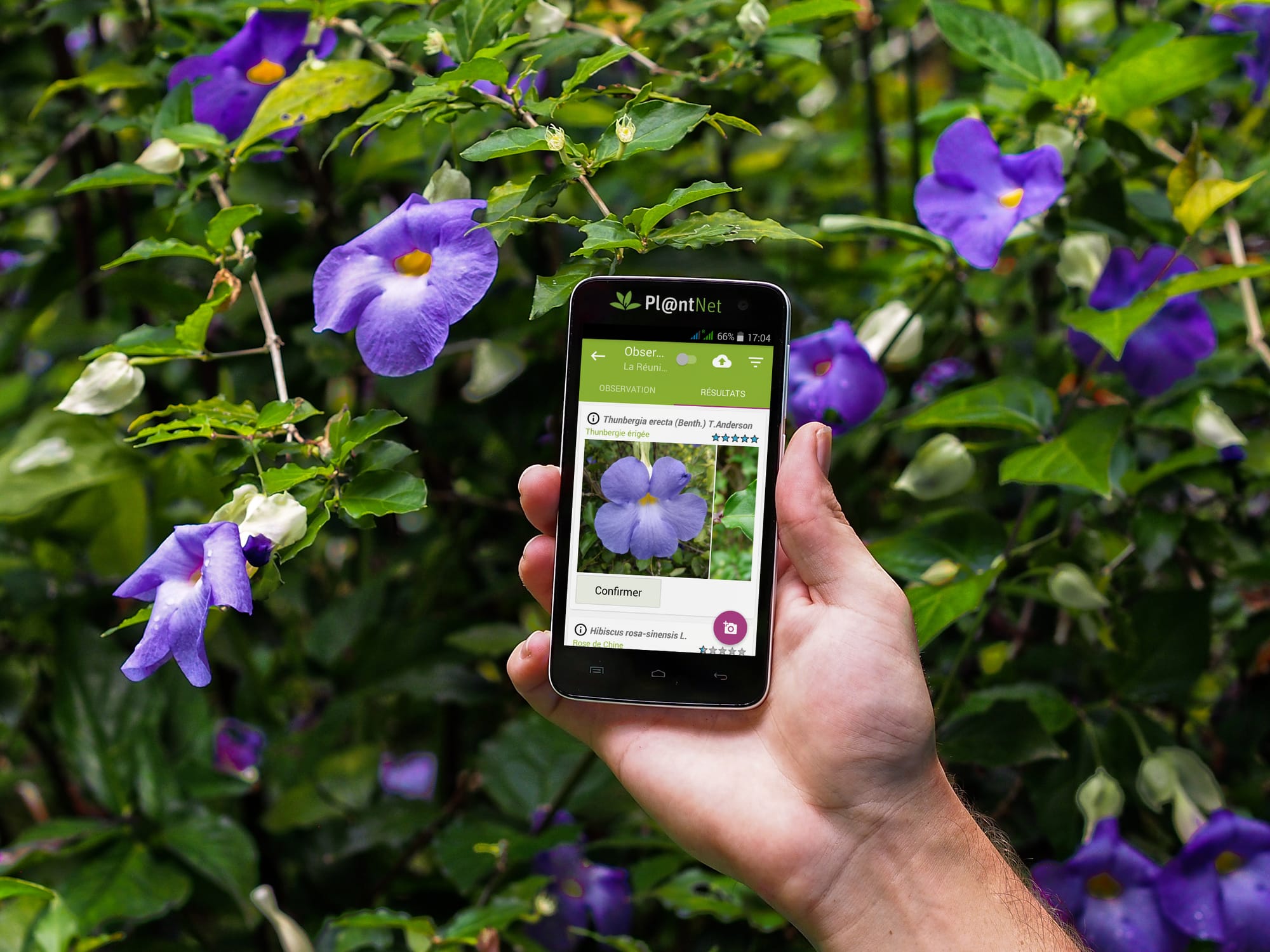

Merlin Bird ID (Left) and PlantNet (Right), apps that help identify birds and plants and feed observations

Here is the simple idea I tested. Use the same tiny computer in your pocket to change what you pay attention to. Call it Algorithmic Mindfulness. Not a gadget. Not a new feed. A habit. The goal is to turn screens into lenses, not shields. When people notice a bird, a reed, a smell, they begin to care in a way no headline can make them care.

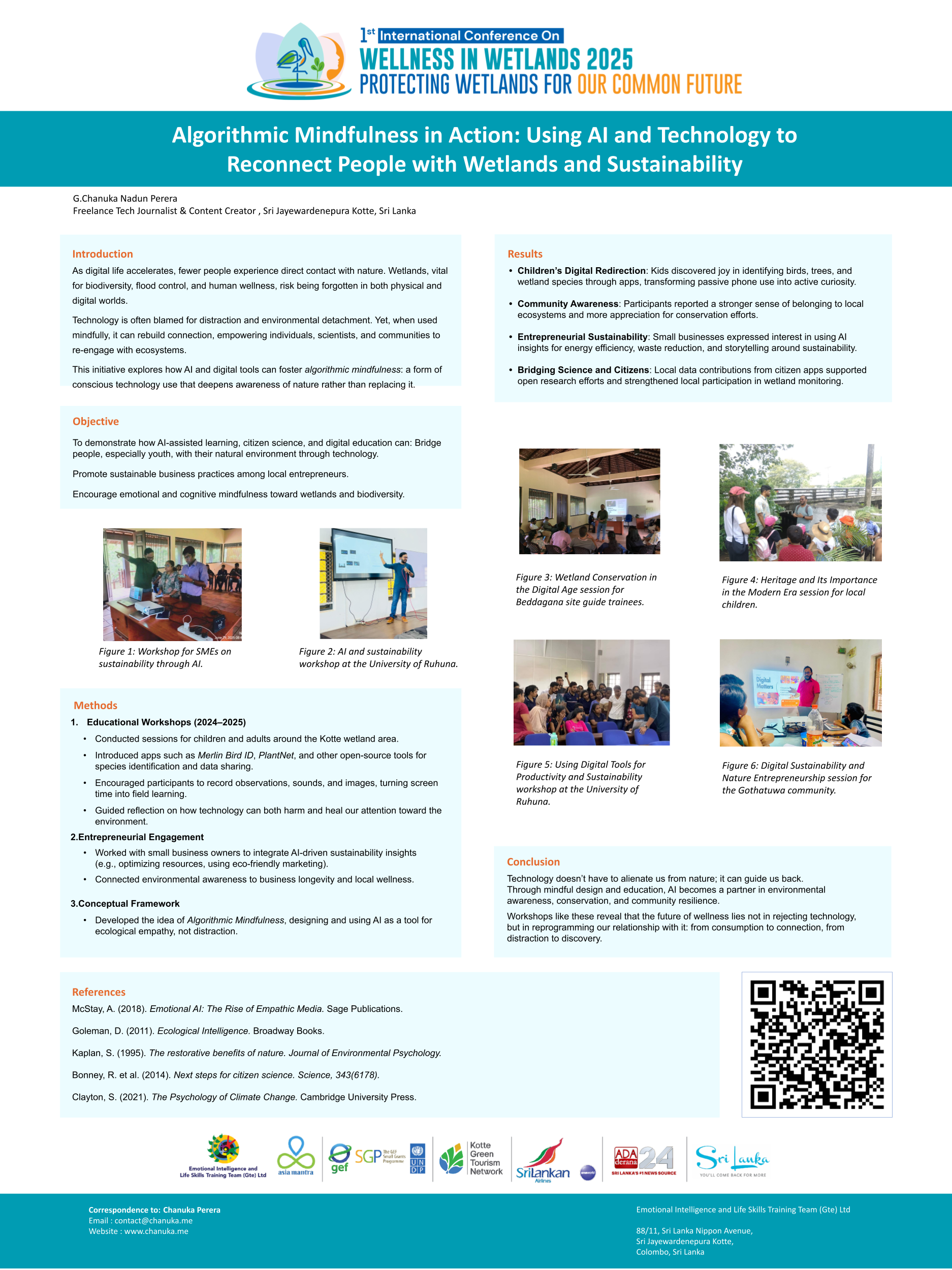

What we did was low-tech and practical. We ran short workshops with schools, volunteers, and small businesses, under a local network that does wetland education and community activities. We taught people to use tools such as Merlin Bird ID and PlantNet, apps that help identify birds and plants and feed observations into global biodiversity databases. Participants were asked to record sightings, sounds, and photos, then submit them. Those records become data for scientists and a running map for the community.

In these workshops, I aimed to help people understand how AI and technology can serve conservation and bridge the gap between people and nature. For example, I used apps that identify bird sounds, trees, and plants, showing how open-source projects like Merlin Bird ID make that information available for scientists. Kids loved it. They are too stuck on the phone, but this time, the phone became a tool to explore. I helped entrepreneurs in the Kotte area think about sustainability and how AI could help them improve their operations while reducing waste.

These activities were not limited to Beddagana. I conducted several related workshops:

- Workshop for SMEs on sustainability through AI

- AI and Sustainability Workshop at the University of Ruhuna

- Wetland Conservation in the Digital Age session for Beddagana site guide trainees

- Heritage and Its Importance in the Modern Era session for local children

- Using Digital Tools for Productivity and Sustainability workshop at the University of Ruhuna

- Digital Sustainability and Nature Entrepreneurship session for the Gothatuwa community

That combination of slowing down, noticing, and then using simple tech does a few reliable things. The wetland itself draws attention. Nature gives what psychologists call soft fascination, the kind that lets the mind recover from directed focus. The act of contributing to a dataset flips helplessness into something measurable: your photo, your record, your point on a map. Citizen science becomes a quiet kind of empowerment.

I conducted several related workshops

Results were modest but real. Children who came to the sessions began using phones to look up species rather than play videos. Adults reported a new sense of local belonging. Several small businesses started asking about low-cost AI tools to trim waste or manage energy. Community groups gained steady local observations that researchers could use. And most importantly, the phone stopped being only an escape route. It became a tool for noticing.

Nature of Americans, 2017 Report

Hickman et al., Lancet Planetary Health, 2021

Susan Clayton, College of Wooster

Urban Development Authority, Sri LankaWorld

Wetland Trust (WLI), 2020

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Merlin Bird ID

PlantNet / GBIF Integration

Bonney et al., Citizen Science Frameworks