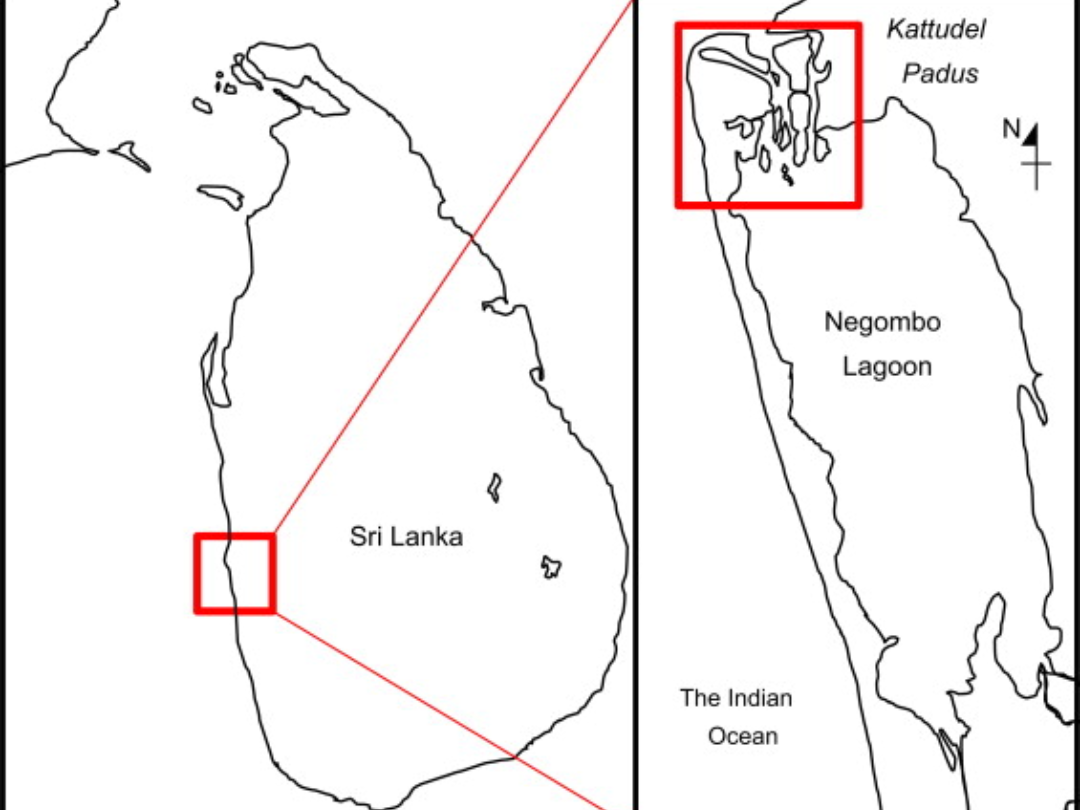

The Padu system, a centuries-old fishing practice deeply rooted in Sri Lanka’s Negombo Lagoon, is more than just a way to catch fish. It’s a living example of community, tradition, and shared responsibility.

For over 250 years, this system has survived, not because of any modern technology, but through strict rules and rotational access that ensure fair use of limited resources. How does something so steeped in tradition continue to survive in today’s fast-paced world?

What Is The Padu System in Negombo Lagoon?

The Padu system has deep roots in the coastal regions of Sri Lanka and Southern India, where it’s been around for centuries. This system, born out of necessity, is designed to manage resources to keep things fair and sustainable for everyone.

This rotational method has been key to the system’s success, especially in the stake net fishery. In the stake-net fishery, fishers plant nets at specific sites known as “Padus.” So, to prevent fights over the prime areas, the Padu system introduces a lottery-based rotational system. Everyone gets their turn to fish in the top spots. (the word Padu means “site” in Sri Lanka and the southern Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu)

Focus on Prawn & Shrimp Fisheries

In Negombo Lagoon, the Padu system primarily focuses on prawns. Commercial prawns are the lifeblood of the local economy. Prawns & Shrimps fetch a reasonable price in the market, and for many of these fishers, catching them is a critical part of making a living.

In Negombo Lagoon, Prawns & Shrimps have always been the main attraction. Their high demand means there’s always a market for them, locally and abroad. But with that demand comes pressure.

That’s why the Padu system is so essential. It helps balance the need to catch enough prawns to support livelihoods while also making sure the lagoon stays energized. The sustainability of this system means fishers can continue to rely on it, year after year, generation after generation, without running the risk of wiping out the very lagoon fisheries they depend on.

How Does the Padu System Work?

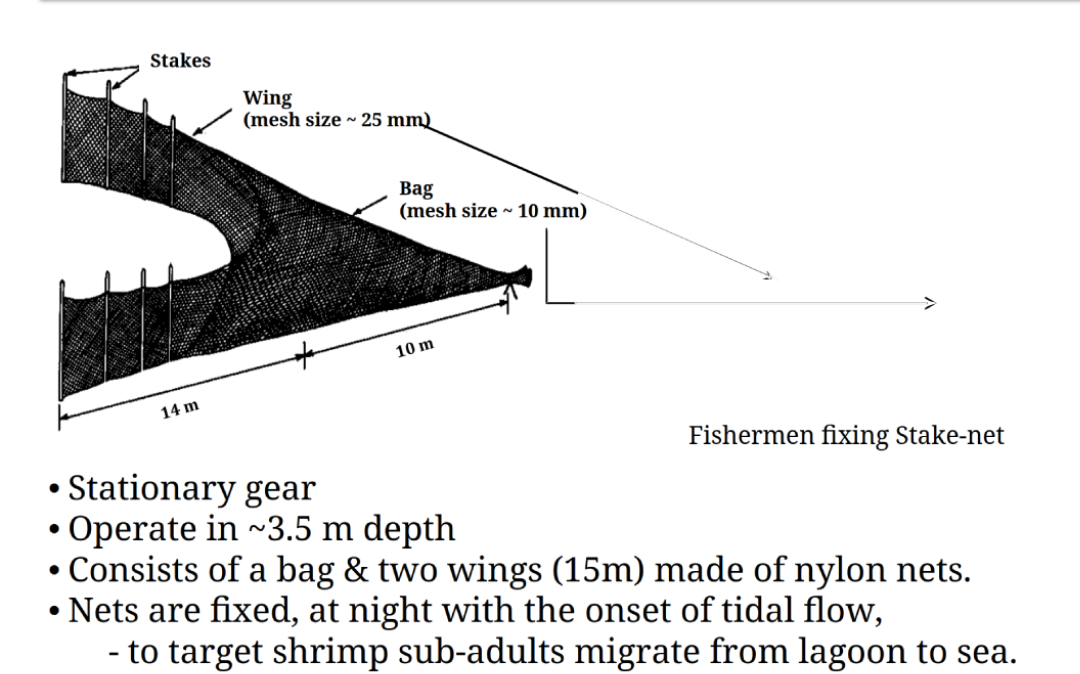

One of the unique things about the Padu system is how it sticks to strict rules around fishing gear. The system is a gear-specific fishery. In this case, it revolves around stake nets specially designed to catch prawns. Everyone has to use the same type of net, with no exceptions. This helps keep things fair because no one can use bigger, more advanced equipment to get an unfair advantage.

The fishing grounds themselves are tightly regulated too. The Padu system has laid out clear boundaries for where fishing can happen, and those boundaries are non-negotiable.

Each site, known as a “Padu,” is essentially a prized fishing spot. Without these rules in place, there would be chaos, with everyone racing to the best spots, depleting resources, and leaving the lagoon in shambles.

Role of Kattudel Fishery Societies

At the heart of the Padu system are the Kattudel Fishery Societies (KFSs), essentially like the neighborhood watch of fishing. These societies manage the day-to-day operations of the fishery and keep everyone in line.

With 294 registered fishers spread across the four KFSs in Negombo Lagoon, the societies play a huge role in ensuring smooth operations.

The access spaces are distributed fairly through a lottery system. This lottery ensures that no one hogs the best spots, and everyone gets their fair share of time in the most productive fishing grounds. It’s an efficient way to manage resources, reduce conflicts, and keep things running fairly and organized. And if you don’t get the prime spot this time, don’t worry; your turn will come around, reflecting the principles of the padu system of community-based fisheries.

Challenges Facing the Padu System

One of the biggest hurdles for the Padu system is population growth. As families grow and more people enter the fishery, the pressure on resources naturally increases. The more people who get involved, the fewer fishing days each member gets.

As the population within the fishing community grows, the system is stretched thin, with each fisher getting less time and fewer opportunities to cast their nets.

But here’s the thing: the Padu system doesn’t just let these challenges run wild. The system has built-in mechanisms to manage the growing number of fishers. One of the ways it does this is through the Kattudel Fishery Societies (KFSs), which keep a close eye on who’s fishing and when.

External Pressures From Illegal Fishers

As if internal population growth wasn’t enough, the Padu system also faces external threats, particularly from illegal fishers. The prawn market is booming, and where there’s money to be made, there are always those looking to bend the rules. Outsiders who aren’t part of the Padu system often try to sneak into the lagoon and take a share of the resources.

The Padu system is vulnerable to these external pressures because it relies so heavily on cooperation and regulation within its own community. When outsiders come in and disrupt the balance, it throws off the careful equilibrium that’s been maintained for generations.

The authorities and KFSs do their best to monitor and enforce the rules, but with limited resources, it’s a constant battle.

Institutional Support for the Padu System

Historically, the church has been deeply intertwined with the lives of the fishers in Negombo Lagoon. It wasn’t just a place of worship; it became the glue that held the community together, especially when disputes arose over fishing rights and territories.

Back in the day, conflicts over who could fish where were frequent and could have easily torn the system apart. But the church stepped in, playing a crucial role in mediating these disputes. Priests would often act as neutral parties, helping fishers resolve their issues without things escalating into full-blown conflict.

They even helped to formalize the system by backing the creation of the “Negombo Fishing Regulations” in 1958. These regulations were a game-changer because they provided official recognition of the long-enduring institutional mechanism of the page system, giving it legal teeth.

Governance Structure

The Padu system governance is structured, almost like layers in an organization, making sure everything is managed efficiently. At the core of this governance is a nested leadership structure.

On the ground, you have the Kattudel Fishery Societies (KFSs) that oversee daily operations, from who gets to fish to where, and enforce the lottery system that allocates fishing spaces fairly. But above them are community and religious leaders who help settle larger disputes or navigate more complex challenges.

Religious leaders, particularly the Roman Catholic clergy, still hold significant influence. The fishers deeply respect the church, and in situations where conflicts can’t be resolved at the community level, it’s often the priests who step in to mediate. The combination of local governance through the KFSs and the higher-level influence of the church creates a balanced system of checks and balances.

Welfare Schemes and Community Support

One of the most reassuring aspects of the Padu system is how Profits from the fishery are distributed. There’s a clear system in place to redistribute these profits back into the community.

Whether it’s a good fishing season or not, the system ensures that some of the earnings are set aside for social welfare, providing a financial safety net for the fishers and their families.

The ways these profits are used are pretty impressive. Healthcare services are often covered, ensuring that fishers and their families can access medical care when needed. Then there’s the pension system, which gives older members of the community a way to retire with dignity after years of hard work.

And let’s not forget about the elderly and those who are physically unable to fish—there’s a provision to support them as well. The community even contributes to religious and cultural events, like church festivals, which help maintain strong community bonds.

The Padu system in Negombo Lagoon, Sri Lanka, stands as a remarkable example of how a community-based fishery management system is essential for the sustainability of lagoon fisheries.

Rooted in local institutional innovation and shaped by the Roman Catholic Church, this gear-specific fishery with strict rules has evolved into a highly structured and adaptable model. The system has become a key player in ensuring fair access to fishing grounds, promoting collective action among right holders in the padu system of community-based fisheries play a vital role in resource management., and offering several implications to sustainable fishery resources management is crucial for the padu system of community-based fisheries..

Despite being under increasing pressure from population growth and illegal fishers, the Padu system continues to serve as a vital economic resource for the fishing population in Negombo Lagoon.

Its institutional arrangements and long-enduring institutional mechanism have helped address fishery adaptation in a way that successfully tackles the commons dilemma. The case studies on this customary marine tenure reveal a wealth of implications to sustainable fishery practices, not only for Negombo Lagoon but for small-scale fisheries across developing countries.

As this system of community-based fisheries management adapts to modern challenges, its design principles aim to address fishery adaptation. co-management approach and multi-level governance continue to foster livelihood sustainability and resource preservation.

The stake-seine fishery model, much like those found in Tamil Nadu and other regions, offers a blueprint for managing fishery adaptation to tackle change and local institutional innovation. common property among resource users.

Ultimately, this article provides several implications for the future of sustainable fishery resources management, highlighting the driving forces of the long-enduring institutional mechanism behind this local institutional innovation.